Recently I described how high school vaping rates reported

in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) are much lower than those

reported in the CDC’s National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) (here). Today I review NSDUH adult vaping rates,

compared to those in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), which is the

CDC’s traditional source for adult smoking estimates.

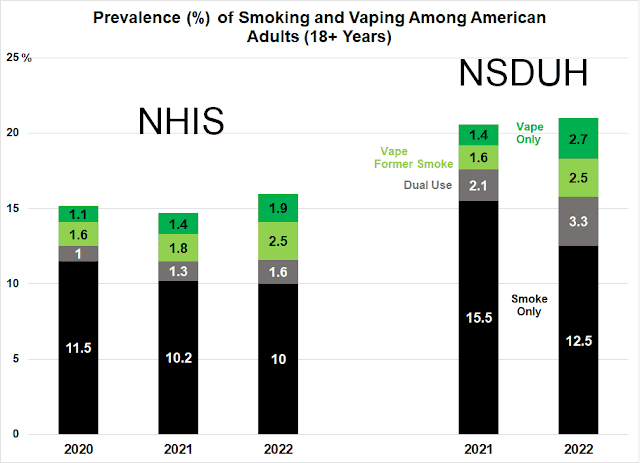

The chart at left shows smoking and vaping rates among all

American adults 18+ years. In 2022, the

NHIS estimate of current smokers was 11.6%, or about 29 million.

Now let’s turn to vaping, keeping in mind that the “Dual

Use” column segments count both current vaping and smoking. In 2022, the NHIS estimate of current vapors was

6%, or nearly 15 million, including almost 4 million dual users.

As I demonstrated in a 2009 published analysis (here),

NSDUH current smoking estimates are always higher than NHIS estimates. Neither survey estimate is right or wrong;

instead, taken together, they probably represent a reasonable range. The 2022 NSDUH percentage of smokers was 15.9%,

or about 39.5 million, while the NSDUH vaping prevalence for that year was 8.5%

or 21 million, with 8.1 million dual users.

Turning to young adults 18-24 years old, in 2022 the NHIS

estimate of current smokers in this group was 4.8% or about 1.4 million, but

the vaping prevalence was even higher, at 15.1%, representing 4.3 million. This means that vaping surpassed smoking among

young adults. The proportions are the

same in NSDUH, even though the numbers are higher: the percentage of smokers is

10.6%, or about 3.7 million, figures that are swamped by the percentage of

vapers, at 24.3%, or 6.9 million.

Why are NSDUH smoking and vaping estimates always higher

than those in NHIS? First, the surveys

ask different questions to account for “current” use. As we noted in our previous

study, “NSDUH identifies almost twice as many some-day smokers as the NHIS,

which is likely due to differences in the questions that subjects are

asked.” But we also discussed an even

more important factor: “the respondents’ perceptions of smoking within the

context of the two surveys. The NHIS is focused on the health status of

participants, with more limited attention on behavioral risk factors. In this

context, smoking may be perceived as one of the more undesirable behaviors that

subjects are asked to report, which may lead to under-reporting. In contrast, the NSDUH is devoted almost

entirely to substance use, with questions about marijuana, cocaine and crack

cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants and non-medical use of prescription drugs. In

the context that these substances are far more socially unacceptable than

cigarettes, participants may be more comfortable acknowledging that they

smoke.”

Fifteen years ago, we wrote, “It is surprising that

estimates of national smoking prevalence have been derived from a single

source, the NHIS, and that little research has been conducted to assess its

accuracy over time… Further investigation of the NSDUH/NHIS discrepancy may

lead to better surveys and an improved understanding of smoking trends in the

USA.”

To date, nothing has been done to explain this discrepancy,

so it is reasonable to consider the NHIS and NSDUH figures as low and high

estimates for U.S. smoking and vaping.