For years we have seen a battle over the banning of menthol

cigarettes. On one side are

prohibitionists, who believe that society’s ills can be cured by proscribing

specific behaviors and products.

Opposing a ban are libertarians and those civil rights advocates who

fear that prohibition would promote illegal sales and consumption, particularly

in the African-American community.

I have commented several times on who smokes menthols (here,

here,

here

and here);

this column was precipitated by a March 22 New York Times article

by Sheila Kaplan, “Menthol Cigarettes Kill Many Black People.”

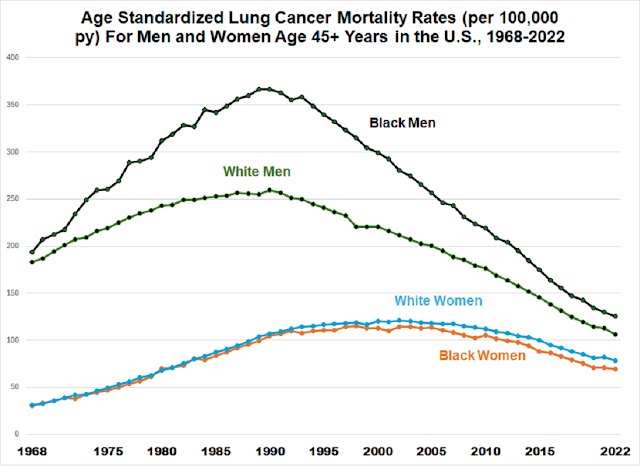

The best way to look at smoking-related deaths is to examine

lung cancer mortality rates (LCMRs), expressed as deaths per 100,000 people per

year. The CDC Wonder website provides

tools for investigating deaths for the period 1968-2022, including

age-standardized rates, so that researchers can compare all of these years,

which had different population distributions.

The chart shows LCMRs for Black and White men and women in

the U.S. Keep in mind that these

mortality rates are latent with respect to smoking, stemming from smoking rates

20 years earlier. For example, when LCMRs

peaked for both Black and White men around 1990, that reflected high smoking

rates from around 1970.

The most striking finding here is that while the LCMR for

Black men was similar to that of White men in 1968, the rate for the former skyrocketed,

peaking in 1989-90 at 367. However,

after that, the rate plummeted every year except one. If menthol was the cause of smoking among

Black men, then it didn’t persist. By

2022, the LCMR among Black men was still higher than that among White men, but

the gap was much narrower.

It’s hard to specify menthol as a major factor, as the LCMR decline

was just as impressive as the LCMR increase.

If, as prohibitionists claim, menthol is easier

to start and harder

to quit,

we wouldn’t see this impressive reversal.

LCMRs were very similar among Black and White women until

around 2000, after which rates among White women were somewhat higher.

Also, note that LCMRs did not peak among women until over a

decade after they peaked among men, and women experience much more of a

plateau, from around 2000 to 2003. And we

still haven’t seen a sharp decline among women yet.

In 2012, FDA Center for Tobacco Products scientist Brian

Rostron published a study finding “evidence of lower lung cancer mortality risk

among menthol smokers compared with nonmenthol smokers at ages 50 and over in

the U.S. population.” (here). These results were in agreement with two

previous studies (here and here).

FDA officials consistently portray a menthol ban as a

corrective response to the tobacco industry’s presumptive targeting of

African-Americans. But, as I wrote

previously, far more Whites smoke menthol.

As for who has been “disproportionately impacted,” Black men have the

highest LCMRs of all four groups, but Black women have the lowest.